As the government finally admits the link between food banks and Universal Credit, Sarah Sinclair meets those let down by the system.

“I don’t know if I’ll get through one day to the next, that’s the honest answer,” admits dad of one, Glen, at Bethany City Church food bank. “If I didn’t have a four-year-old girl I wouldn’t be sitting here having this conversation, I’d be six foot under the ground, without a shadow of a doubt. I’ve even considered that anyway, because it’s so hard.”

Having been employed as a contractor for the last 20 years, Glen, from Sunderland – who didn’t want to give his surname – would never have imagined that he’d be forced to rely on a food bank to feed his family. In October 2018 he found himself out of work and applying for Universal Credit. Almost four months after he first entered the system, he is yet to receive a penny. As he sits opposite me, sipping tea from a paper cup in the church’s community cafe, Glen’s despair is palpable.

“I didn’t expect to be in this situation, certainly not,” he confesses. “None of my family and friends would have any idea that I was here, it’s not a conversation I would have, it’s not a conversation I believe I should have, nor probably anyone else in this room. Whilst I don’t know everyone’s individual circumstances, they are probably in here because one way or another they are not getting what they are entitled to.”

Unfortunately, Glen’s story is just one among many at the church in Ashbrooke. The food bank deals with over 60 per cent of all referrals across Sunderland and over the last year it has been a lifeline for almost 4,000 people.

Anyone can find themselves this desperate. Ashamedly, I was taken aback on arrival, when a man approached me to ask if I was there to collect a food parcel. But at 4pm on a Wednesday, I am one of few here who is not. With the numbers of users rising expeditiously, the common misconceptions about those who rely on food banks are far off the mark. The Trussell Trust food bank network’s latest statistics show a 13 per cent increase, with more than 1.3 million three day emergency food supplies issued nationally, from 2017-2018. Over half of referrals to Bethany City Church last year were a result of benefit changes or low income.

“We find the biggest reason of referral is because of Universal Credit,” says Assistant Church Pastor, Daniel Alcock. “We get people coming in suicidal, like genuinely, really needing help, once a week now, at least.”

He cites Universal Credit as a contributing factor. “For some people it’s the thought of being homeless for the first ever time, is just soul crushing,” he adds.

Andrew Hedley, 46, from Ashbrooke has been on Universal Credit for three years. He was a regular at the food bank before becoming a volunteer himself. It’s the sense of community here has kept him going.

“It’s had its ups and downs,” he says of his experience of the system. “The ups are coming out and mixing with the community, but the downs are that you’re always thinking about your last week, when you’re getting paid. It’s from the third week onwards, you’re struggling for that last week before you get paid again.”

He continues: “They’re saying it’s a good idea, but who for? Is it for the government or the people? Because it’s not for the people.”

This month in parliament, Sunderland MP Sharon Hodgson secured an admission from the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Amber Rudd, that the rise in food bank usage across the UK is linked to the roll-out of Universal Credit. This is the first time the government has acknowledged this connection.

Cllr Geoff Walker, Cabinet Member for Health and Social Care at Sunderland City Council, blames the governments’ preoccupation with Brexit for the mistakes which have been made in the roll-out of the system. “It’s good to hear that Conservative ministers can realise the connection between their maladministration and the rise of food banks,” he comments. “All this time now we have been engaged in this ridiculous to-ing and fro-ing with Brexit and a lot of stuff on the health and social care front has just fallen by the wayside. A lot of administration hasn’t been dealt with correctly, including Universal Credit.”

But for Head of Sunderland Food Bank, Kate Townsend, the admission comes too little, too late. She says: “It’s good that this has been admitted because it means that they have to do something about it. They should have admitted it months ago. It shouldn’t have come now when millions of lives have already been affected.”

Last month, Sunderland Food Bank saw an overall increase in demand, believed to be a result of the roll out of Universal Credit in the city in July last year. Kate explains: “The January statistics – the number of people that we fed – has massively increased from what we were feeding before Universal Credit was rolled out.”

Many, including Kate, believe that the five week transition period from legacy benefits to Universal Credit is too long, and The Trussell Trust – which Sunderland food bank is a part of – is currently campaigning to end the five week wait. It is this delay that is leaving people struggling to make ends meet, falling into debt and being forced into food banks.

Assistant Pastor, Mr Alcock also wants to see this period reduced. He said: “Thirty-five days is a long time to wait if you’ve just lost your job; you’ve got no reserves in the bank; you’ve got a mortgage; you’ve got kids,” he says. “It doesn’t take much for someone to find themselves in need of a food bank.”

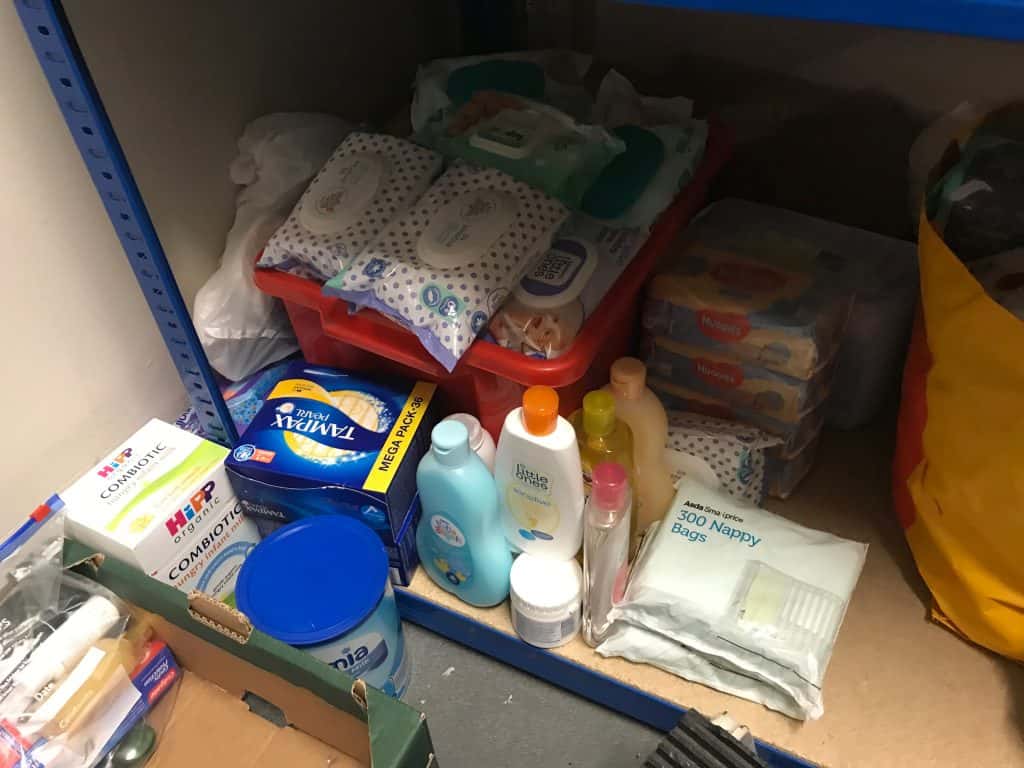

Before I leave, he shows me where they make up the food packages. As well as the shelves stacked with tins, cereal packets, toiletries and tampons, there are rails of warm coats and boxes of sleeping bags which are given out to those who are left, literally, out in the cold.

“It really breaks my heart when you see families with kids coming in,” Daniel adds. “We always put more sweets in the food parcels when we see kids are on the list.”

Andrew was right about the sense of community at Bethany City Church. I get the feeling that the people here rely on each other as much as the food parcels they give out. Over a cup of tea and a shortbread biscuit they’ve built bonds over the one thing they all have in common; being let down and left behind by a system that’s not fit for purpose.